Last week, I introduced some critiques of ‘model-centric’ AI companies, and implications for economics and product strategy. For Part 2 here, we’ll get a bit more tactical on fine-tuning vs. model routing, then tie off some threads on making your AI business and investing strategies more anti-fragile.

“A word is worth a thousand vectors.”

Given the choice, would you rather be a well-trained expert who stays in their lane, or have the raw intellectual horsepower to master anything?

Back when I took CS224N at Stanford, before the transformer era, Prof. Chris Manning blew our minds with a simple demo. Using an embeddings model, he showed us how semantic concepts like “royalty” or “gender” could be reduced to arithmetic operations in vector space, e.g. “king is to queen as man is to woman” (woman = queen - king + man). We spent the next hour testing increasingly complex analogies across many domains - book genres, clothing styles, occupations - and in each one, the model generated outputs that seemed, well, weirdly intuitive.

This was a glimpse into how models perceive language, not as siloed domains, but as an interconnected web of concepts, with clusters and intersections that we can’t naturally envision… or as Chris Moody so pithily put it, “a word is worth a thousand vectors.”

I thought about this a lot as last year’s meme of ‘domain-specific models’ took off. What constitutes a domain that deserves a specific model? Are the differences we perceive between subject matters so complex that a fine-tuned model is typically the best solution?

This question is at the heart of many Fortune 500 companies AI strategies, and I’m not sure they’re going to like the answer.

Your data (probably) doesn’t matter

Unfortunately, fine-tuning your own <Company Name>GPT might be a waste of time.

My consultant friends wouldn’t want me telling you this, but beyond some baseline of model intelligence, your data probably doesn't matter that much. While fine-tuning can be useful for consistent output formats or learning certain styles, most businesses' datasets aren't unique enough in language vector space to warrant the investment.

Take BloombergGPT, for example. Despite costing $10M to build and being trained on 51% proprietary Bloomberg financial data, its initial performance edge was quickly eclipsed by GPT-4 without the latter using any special Bloomberg sauce, just a larger parameter count and more compute.

Harvey may have followed a similar playbook. Raising $21M just a month after BloombergGPT’s release, with nearly half the headcount comprised of expensive lawyers, and insisting on a hefty user-based pricing model ($1200/seat/year, 100-seat minimum), they’re betting big on fine-tuning, prompt engineering, and negotiated lock-in. But as a viral teardown by Edward Bukstel suggests, chances are Harvey spent a ton of money fine-tuning a model that newer ones already outpaced with RAG and/or agentic systems.

Might be reading into the tea leaves too much, but this sounds to me like an incredibly expensive endeavor fighting last year’s battle.

In both cases, The Bitter Lesson rings true - the biggest breakthroughs in AI tend to come from simple, scalable architectures, vs. bespoke tweaks that yield short-term improvements.

Models as utilities

Instead of building bespoke models that introduce complexity, simplifying how we interact with other peoples’ models is the bigger prize.

When Andrew Ng talks about how “AI is the new electricity,” here’s how I think about it: We need electricity for lots of things. Kitchen appliances, lighting, television, tons of applications. But ultimately, does my nephew care that our TV uses electricity which comes from a utility that uses 100% renewable energy? No, he just cares that he can watch Bluey on it.

However, as the one paying for the electricity, I definitely care about variables like price, availability, and climate-friendliness. I fortunately come from a state where consumers can pick their provider based on these variables, and that transparency creates a more competitive market that ultimately benefits me, the consumer. Although I now live in a state where this choice isn’t available, and outside of regulatory action, PG&E’s monopoly gives it little incentive to do anything besides raise rates, even in bankruptcy.

Right now, there are dozens of competing large models, each hosted by dozens of token-as-a-service providers, all of whom are competing with each other based on price, quality, climate-friendliness, data privacy, many other variables to win your business. This is a hugely beneficial time to be building if you know how to play these providers off each other.

You’re welcome to lock in to a single provider who has your preferred ecosystem, but you’re SOL if the price jacks up or there’s an outage. You’re also perfectly capable of setting up your own server, just like you could install solar panels on your house, but that carries maintenance costs many would rather not worry about.

To my nephew, playing Bluey is the TV’s only job. He’s not going to be very impressed with my off-the-grid solar array if it’s cloudy for more than a few days.

Routers are an ROI multiplier

So if sinking millions into fine-tuning models might not work for most businesses, and you want to avoid the hostile user-based pricing, what’s the alternative?

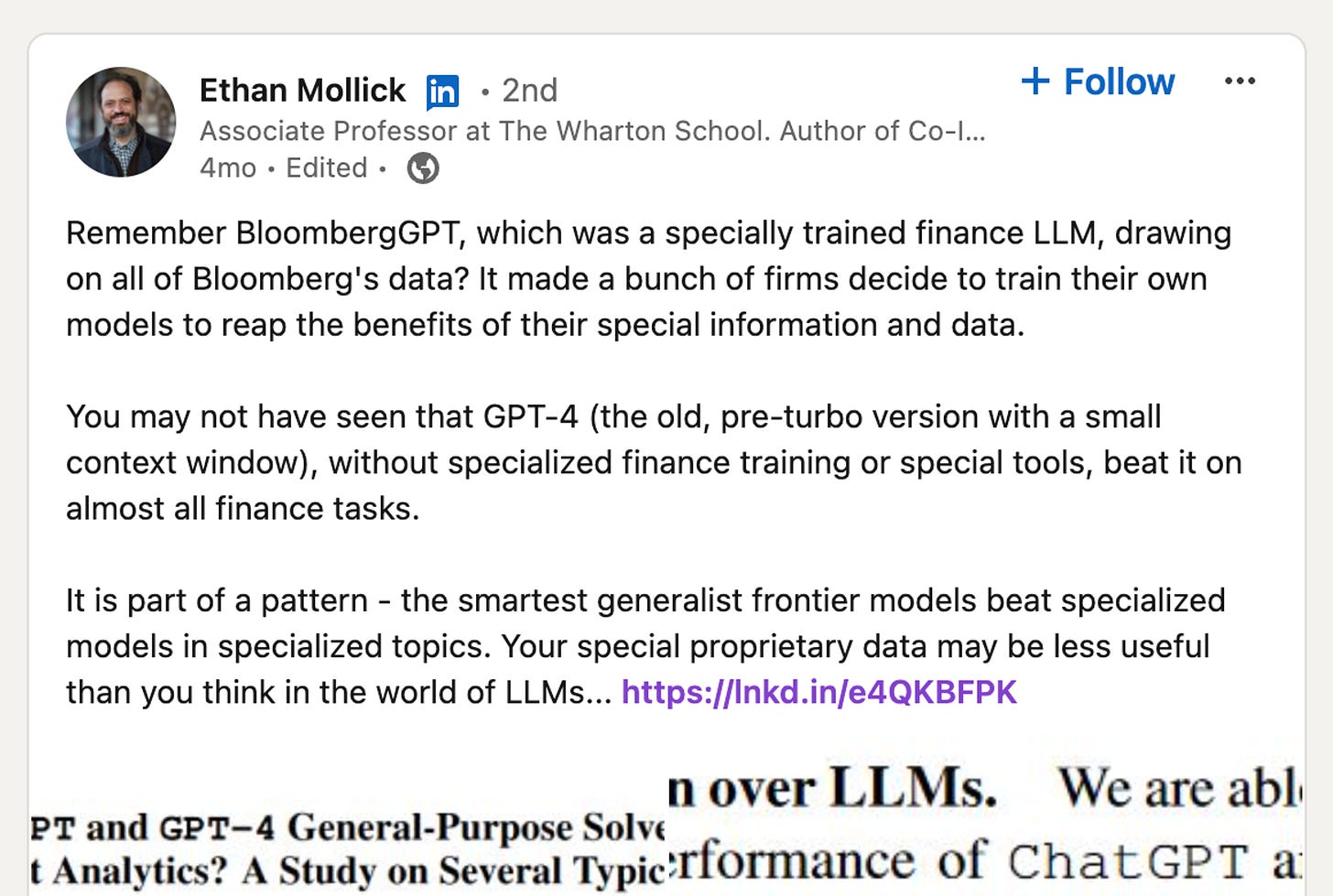

Model routers like Martian and OpenRouter are promising, anti-fragile solutions which deliver all the benefits of a competitive model marketplace with minimal complexity.

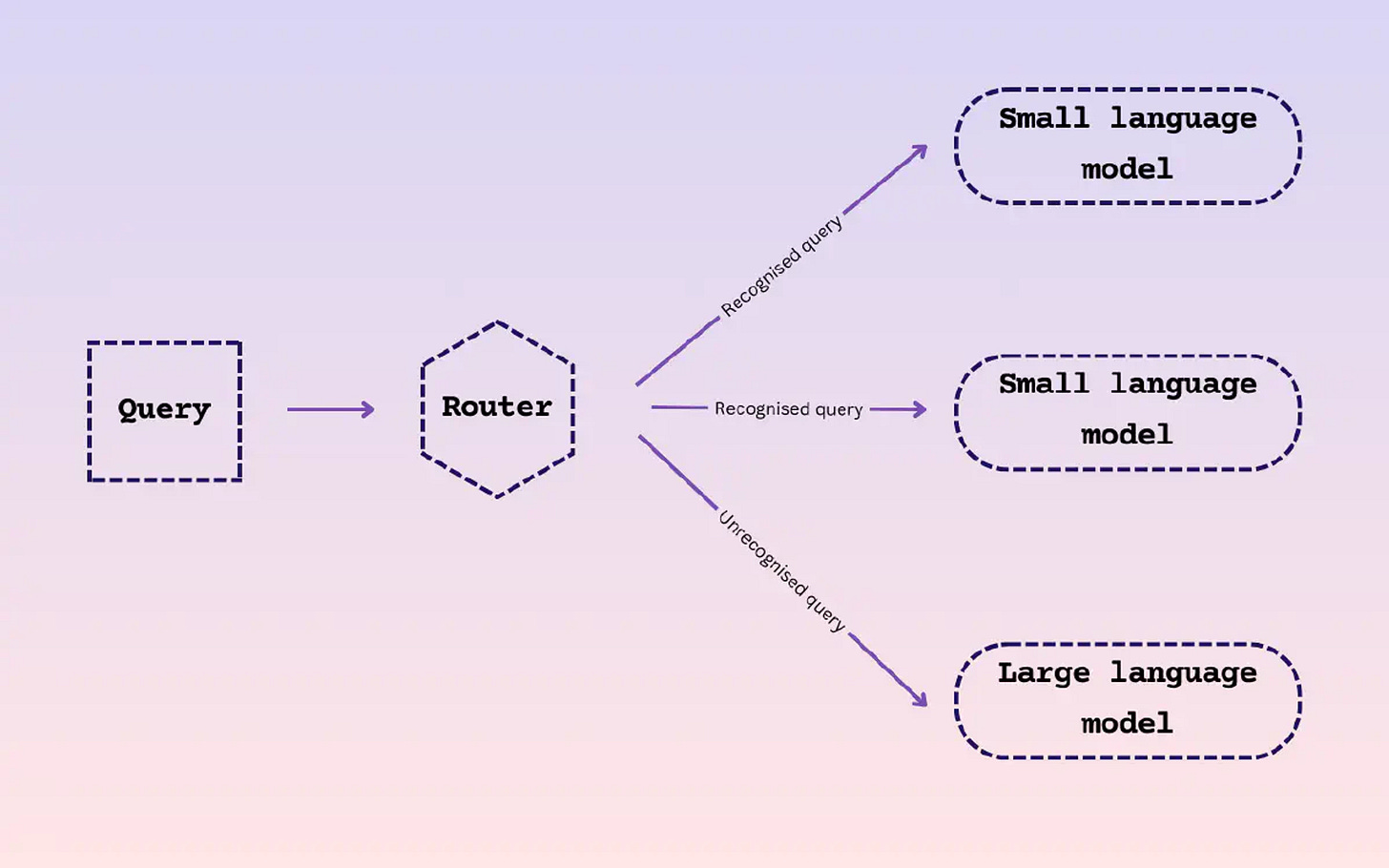

Rather than getting locked into a single model and praying your vendor doesn't jack up prices (or get dumber), routers use special techniques to dynamically send prompts to whichever model is best suited for it. To be clear, this is much more fine-grained than saying “Model X is best for <Domain Y>” - this is task-specific prompt → model routing.

The net effect is that you get orders of magnitude reductions in inference costs while enjoying the same (or better) quality results that larger, expensive models would return.

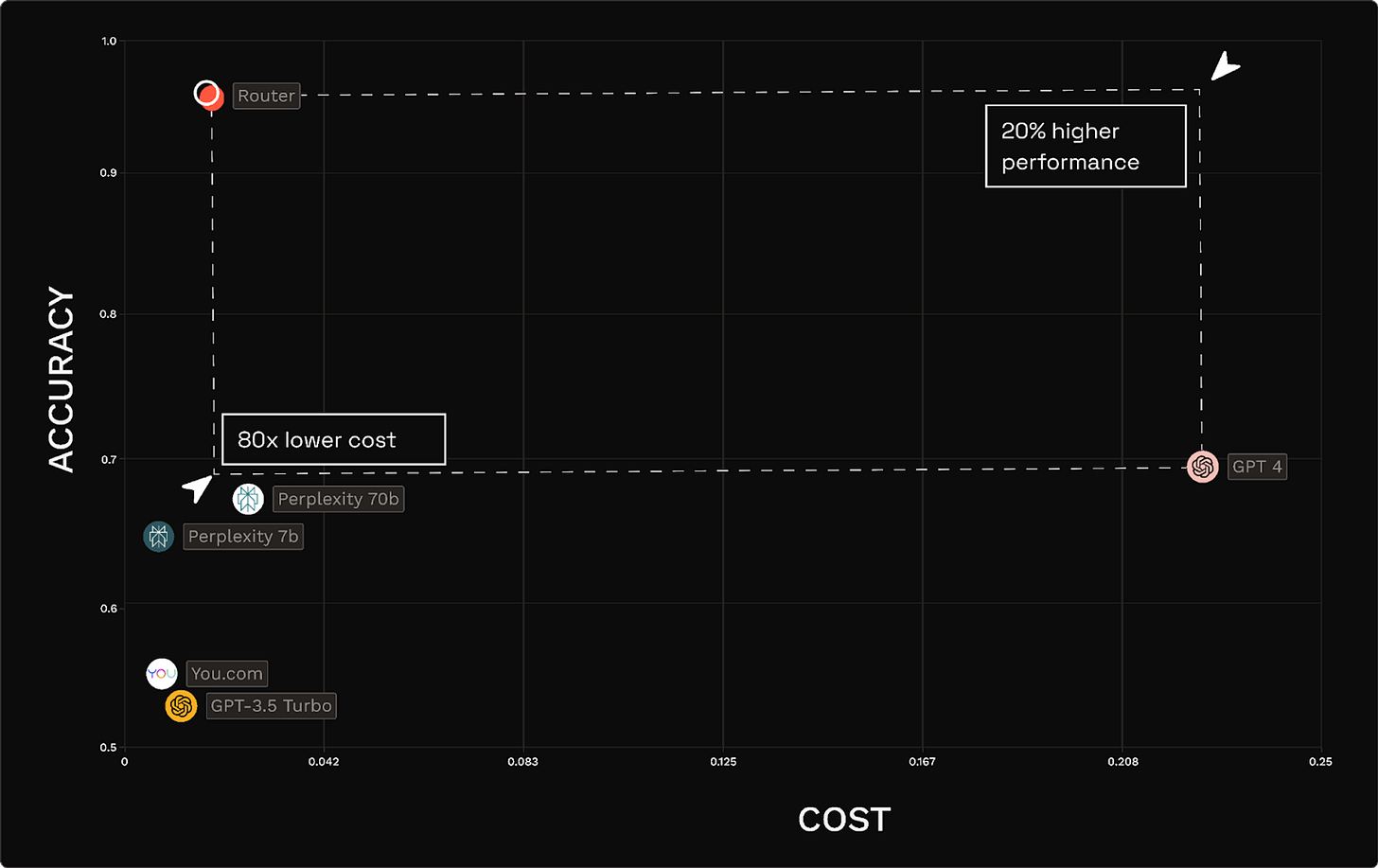

Under the hood, routers are built on datasets of pairwise comparisons between model outputs in response to a query. Prompts are assigned a high-level category, such as asking_how_to_question or text_correction, and human raters (or GPT-4 in some cases) select the best output.

Overtime, a representative corpus of qualitative comparisons between models is built, which can then be used to categorize prompts, then route those prompts to the best performing model for that category. Platforms like Chatbot Arena are great for this, though its category granularity could be a bit better.

However, that’s just for qualitative comparisons. Deployment teams may want to optimize for speed if latency is a success metric, or cost if spend reduction is the primary goal.

Many organizations (including OpenAI, if the rumors are true*) leverage model routers internally to optimize their inference costs; they route “simpler” requests to smaller models that are much cheaper to run (but lack sophistication), and route more complex, thoughtful prompts to more expensive models better equipped to provide helpful responses. These dynamic systems can significantly outperform any single-model system on multiple dimensions.

* This is at the center of the “GPT-4 is getting dumber” meme. At a new model’s launch, OpenAI would want all prompts to deliver high-quality results to connect its brand to consistently high intelligence. But not all prompts are created equal. At full optimization, dumb questions get <proportionate> answers from lower-parameter model variants.

Getting started

Whatever system you end up using, you should definitely be capturing user prompts, outcome ratings, and other metadata for your own analyses later. This will help RLHF better routing systems over time, tailoring them to your specific application, and contributing to defensibility against unoptimized wrapper and single-model competitors.

You may also find certain tasks are consistent and frequent enough to justify creating your own small language model (SLM) to serve them. This targeted approach can compound inference cost savings even further.

If you're interested in exploring model routers for your own applications, the team at Pulze AI has generously open-sourced their intent-based router, comparison dataset, and intent embedding model, which are great starting points for teams looking to roll their own solutions.

Wrap-up

Given that “almost everyone is losing money on LLM inference,” the anti-fragile approach model routers offer is pretty refreshing. While everyone else seems to be rushing to build ever-larger generalist models or domain-specific models, you might want to leave that particular race to the well-funded labs draining VCs dry.

Model routing isn’t just a technical solution - it’s fundamentally democratizing, as it encourages more, not fewer, models to be built. Instead of raising billions for a generalist model only to fail, as Inflection did, devs can build niche specialist models that plug into a routable model marketplace. If they’re objectively better, they’ll be used and yield a profit.

Make no mistake, that doesn’t mean every specialist model constitutes building a venture-scale company around it. And I don’t think “LLM for Finance” or “LLM for Legal” counts as “specialized.” But in aggregate, a constellation of LLMs, SLMs, and task-specific agents, stitched together by a robust routing layer, starts to look an awful lot like the future of the field.

For more on routers, check out Cerebral Valley’s Martian deep dive into Martian, where founders Yash and Etan share their inside story.